On December 26, 2004, the world witnessed the devastating impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami, a calamity that claimed an estimated 227,898 lives across 14 countries, including Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand. Triggered by a colossal undersea earthquake with a magnitude between 9.1 and 9.3, this catastrophe caused waves as high as 30 meters (100 feet), wreaking havoc on coastal communities. Recognized as the deadliest natural disaster of the 21st century, this event underscored glaring gaps in early warning systems, drastically altering global approaches to disaster preparedness.

The magnitude of destruction prompted international collaboration, scientific innovation, and infrastructural development aimed at preventing future disasters of similar scale. These advancements provide insight into how the 2004 tsunami became a critical turning point in the development of early warning systems and disaster mitigation strategies worldwide.

What Were the Key Weaknesses Exposed by the 2004 Tsunami?

Before 2004, many countries in the Indian Ocean region lacked adequate systems to predict and respond to tsunamis. For instance, Indonesia, one of the worst-hit nations, was without crucial data on sea surface levels, leaving experts unable to “see” the wave forming. Unlike the well-established Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, the Indian Ocean region had minimal infrastructure for early detection or communication of threats.

- Absence of Real-Time Monitoring: The region had only one sea-level monitoring station, which was grossly inadequate to detect rapid water-level changes.

- Underdeveloped Technology: Detection methods and algorithms were too slow to provide timely warnings. In 2003, experts required 15-50 minutes to confirm an earthquake and its tsunamigenic potential, an unacceptably long delay given how rapidly waves can travel.

- Inadequate Communication Systems: Many vulnerable communities did not have direct channels for receiving warnings. This lack of communication left millions unaware of the impending disaster.

What Technological Advances Have Improved Early Warning Systems Since 2004?

The aftermath of the tsunami led to an unprecedented push for creating robust early warning systems, emphasizing technological advancements and global collaboration. Today, these systems leverage cutting-edge tools for monitoring seismic activity and water-level changes, significantly enhancing preparedness.

- Expansion of Monitoring Stations: The number of sea-level monitoring stations has grown from just one to an impressive 14,000 globally, offering real-time insights into water-level changes.

- Introduction of DART Buoys: Around 75 Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) buoys now operate in all oceans, detecting minute pressure changes on the seafloor to predict tsunami formation.

- Improved Algorithms: Advancements in algorithms have drastically reduced detection times. Experts can now confirm an earthquake’s potential to generate a tsunami within five to seven minutes, compared to over 15 minutes two decades ago.

- Faster Supercomputers: Enhanced computing power allows for rapid modeling of earthquake and tsunami scenarios, enabling better risk assessments and faster dissemination of warnings.

Laura Kong, director of the International Tsunami Information Center, remarked that the ability to provide warnings before waves reach land has been a game-changer. This capability has significantly improved the chances of saving lives in future events.

What Global Efforts Have Been Made to Strengthen Preparedness?

In response to the 2004 tragedy, the United Nations spearheaded initiatives to develop and implement early warning systems across vulnerable regions. The establishment of the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (IOTWS) was one of the most notable achievements, built through international collaboration led by UNESCO.

- IOTWS Operations: The system comprises 25 seismic stations, 12 Bottom Pressure Recorders (BPR) capable of detecting 1 cm water-level changes in depths of up to 6 km, and a network of 50 tide gauges to track tsunami progression.

- Communication Networks: Alerts generated by IOTWS are shared through various channels, including Cell Broadcast messages, SMS, radio, and television broadcasts, as well as sirens and public address systems.

- Regional Collaboration: Countries like India, Indonesia, and Australia have taken leading roles in monitoring seismic activity and issuing regional alerts, ensuring faster response times.

Additionally, capacity building has become a crucial focus. Efforts include training programs for local authorities and communities, as well as the creation of coastal vulnerability models and inundation maps to assess potential impacts of future tsunamis.

What Challenges Still Persist in Disaster Preparedness?

Despite remarkable progress, significant gaps remain in the global effort to mitigate the impact of natural disasters. A report by the United Nations highlights that over half the countries worldwide lack effective early warning systems, even for routine events like cyclones and rainfall. The burden of this shortfall falls disproportionately on developing nations, where climate-related disasters cause 15 times more deaths than in wealthier regions.

- Limited Access to Technology: Many developing countries struggle to acquire and maintain the sophisticated equipment necessary for modern warning systems.

- Communication Barriers: Even when warnings are issued, they often fail to reach remote or underserved communities due to inadequate infrastructure.

- Vulnerability to Secondary Hazards: Early warning systems are primarily designed for tectonic events, leaving regions exposed to other risks such as tsunamis triggered by volcanic eruptions.

The 2018 Sunda Strait tsunami in Indonesia, caused by a volcanic eruption, underscored these challenges. In response, additional sea-level sensors have been installed to address this gap. However, further advancements and investments are needed to ensure comprehensive coverage.

How Has India Strengthened Its Disaster Response Capabilities?

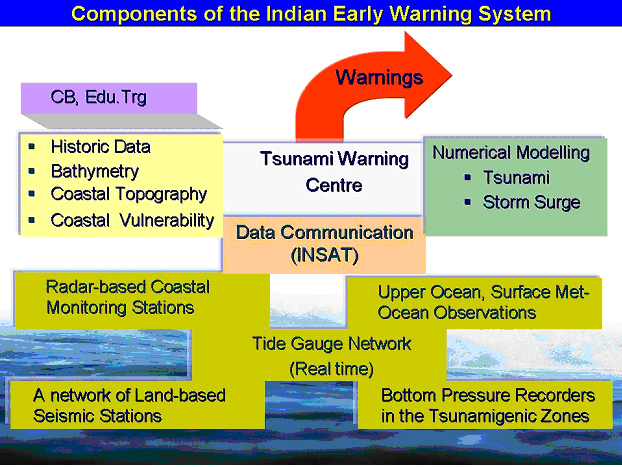

India, one of the nations severely affected by the 2004 tsunami, has made substantial progress in developing its disaster response mechanisms. The Government of India assigned the responsibility of creating an advanced Tsunami Early Warning System to the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services (INCOIS) in Hyderabad. Today, India boasts one of the most sophisticated tsunami warning infrastructures in the region.

- Real-Time Seismic Networks: INCOIS operates a 24/7 Tsunami Warning Centre, supported by a network of seismic stations capable of detecting tsunamigenic earthquakes in real-time.

- Monitoring Equipment: The system includes 12 Bottom Pressure Recorders and a range of tide gauges and radar-based coastal monitoring stations to track tsunami activity.

- Forecasting Capabilities: Real-time observations of oceanic parameters and high-resolution databases on coastal topography and land use are used for accurate storm surge forecasts and vulnerability assessments.

- Public Awareness Initiatives: Regular training sessions, educational campaigns, and mock drills have been conducted to ensure that stakeholders and communities understand how to respond to warnings effectively.

These advancements have not only enhanced India’s ability to safeguard its citizens but also contributed to regional safety by sharing information with neighboring countries.

What Lessons Has the World Learned from the 2004 Tsunami?

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami served as a stark reminder of the need for comprehensive disaster management systems. It revealed that even modest improvements in warning capabilities can save thousands of lives. For instance, research by the World Meteorological Organization indicates that providing just 24 hours’ notice of an impending tsunami can reduce damages by 30%.

The global response to this disaster has underscored the importance of international collaboration, technological innovation, and community resilience in minimizing the impacts of future events. While significant strides have been made, addressing the persistent gaps in preparedness and ensuring equitable access to these life-saving systems remain critical challenges. By continuing to learn from past experiences, humanity can strive toward a future where the devastating impacts of natural disasters are significantly reduced.